🔺Listen to the essay🔺

📚 Buy the Book → Right Kind of Wrong

The first substantial book I read was The Lord of the Rings. I didn’t read it out of a love for fantasy or storytelling. I read it for Accelerated Reader points. One book to rule them all, aka I could meet the entire yearly requirement.

The journey of Frodo spans a little over a year, but the entire fate of Middle-earth changes during the same span. Centuries of buildup all come to a head and resolve within a narrow window of time.

It’s not about how long something takes but rather how much can happen within a compressed time.

This theme exists beyond the covers.

Progress becomes a matter of iteration based on feedback, rather than time spent. It comes from tightening the feedback loop.

The faster the cycle, the greater the advantage.

It’s Not the Hours. It’s the Cycles.

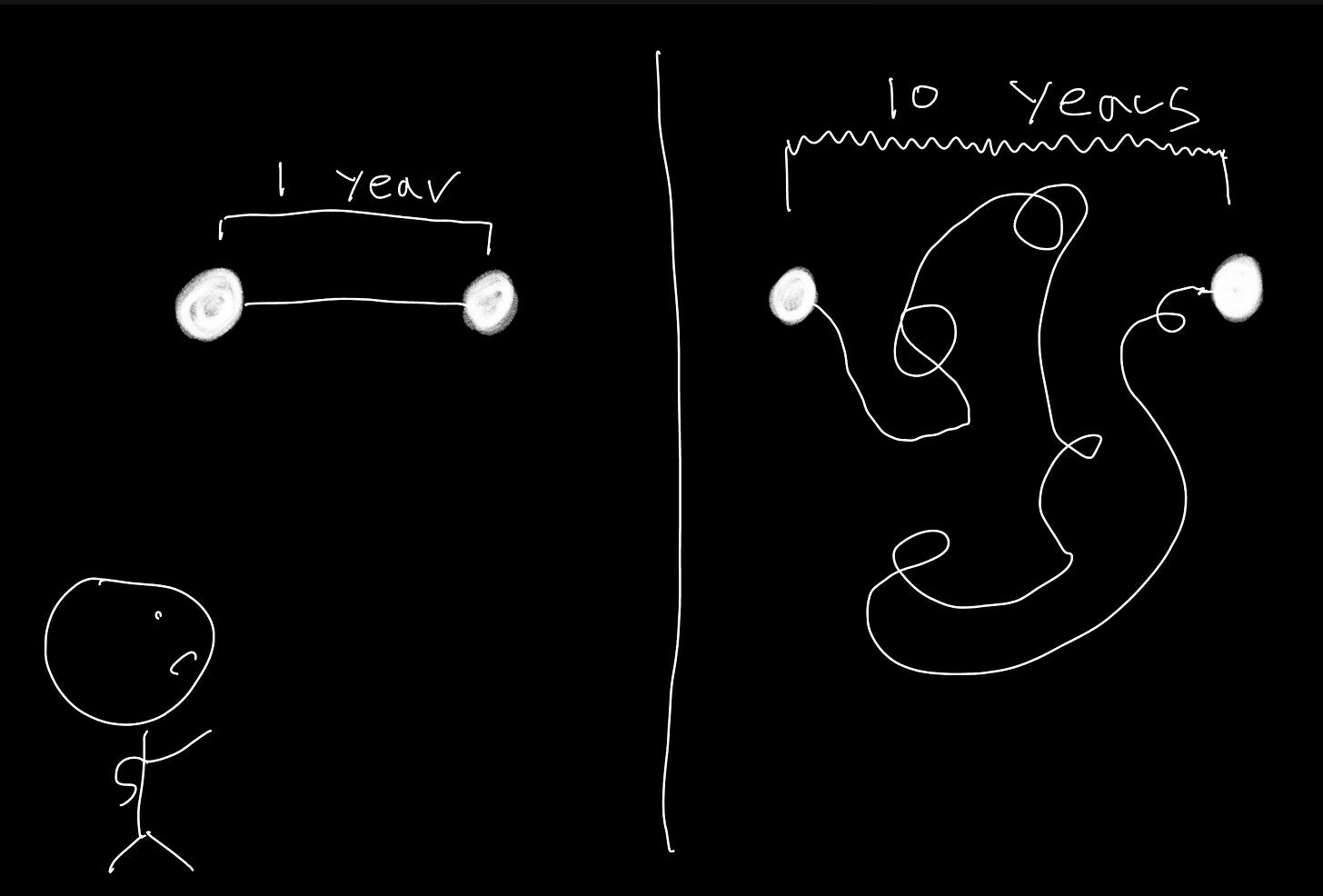

It’s not about raw time. It’s about how fast you move through cycles of improvement.

That’s a subtle but important distinction.

Many people still equate time spent with progress made. But that view can be misleading. It's not about how much time you invest. It's about how quickly you can cycle through doing, learning, adjusting, and doing again.

If time is the input, then iteration is the engine.

Compressing the time between iterations is what creates leverage.

“Success doesn’t come from 10,000 hours. It comes from 10,000 iterations.”

- Naval Ravikant

Henry Ford’s assembly line highlights this leverage. Before Ford’s implementation of moving assembly lines, building a car once took over 12 hours. Ford brought that down to about 90 minutes. This compression of time gave Ford his fortune, and it gave the middle class access to mobility.

This mobility was crucial in enabling many Americans to pursue economic opportunities and fundamentally changed the way people lived.

Today, many businesses follow time compression as their main strategy and sometimes their only one.

Take fast fashion, for example. What traditional clothing brands took months, fast fashion brands such as Zara took just a few weeks. Time compression as a strategy enabled them to test what works and adapt quickly to demand.

While fast fashion has a low regard for sustainability and labor, it reveals how the compression of time between idea and execution can lead to dominance, at least in the short run.

This goes beyond the materialistic world.

The Tightest Loop Wins

Time compression operates as an undercurrent to everyday life.

Google is a straightforward example of time compression. Something that required a trip to the library can now be answered in seconds. The search engine tightens the loop between question and answer.

This is currently being disrupted by AI, where it’s making the distance between question and answer even tighter.

TikTok’s algorithm is one of the best time compression algorithms out there.

It takes a mere few swipes to learn about a new user. It can solve the cold start problem quickly through micro-signals. The tightening of the loop between signal and personalization creates a strong competitive advantage.

Greenhouses compress agricultural time cycles. It gives us strawberries all year round. What used to be dependent on weather and geography is no longer limited. Reducing the time between planting and harvesting.

The materials we use, the systems we live in, and the platform we rely on are often built on the principle of time compression. Faster cycles between input and outcome result in a structural advantage.

This same principle governs the well-being of individuals.

Closing the Loop

At first glance, time compression might look like a productivity trick. But that framing misses the point.

Time compression is really about removing friction from the learning cycle.

It’s about increasing the rate of refinement.

Sometimes, compression is a matter of luck. A friend of mine landed a job in six weeks. For others, it may take six months.

That’s a 147-day difference. A head start like that can quietly compound.

Other times, it’s the result of effort. One person might iterate five times in the same period, another takes to get through one cycle. Even with equal starting points, their trajectories begin to diverge.

Some people earn six figures in their twenties. Others do it later.

Some never get there at all. Often, it’s not just a matter of talent or will.

It’s about who gets to cycle through learning more often, more quickly.

In markets and in life, we don’t control the hand we’re dealt, but we do have some influence over how often we play and how quickly we learn from each round.

In the past, the edge belonged to those with more capital, more experience, or more time. Increasingly, the edge belongs to those who compress the space between effort and feedback. Some wait years to begin. Others start early and refine as they go.

Over time, those choices create distance.

Time compression is a principle, and like most principles, its value becomes more apparent with time.

So it may be worth asking:

Where in your life could the learning loop be shorter?

That’s where the leverage tends to live.

⭕

Exclusive Essays

Private Podcast Episodes

The Full Library

For the Joy of Learning,

Su Hawn

🏕️ Life Happens Outside: Leverage - Florida Keys, USA