📚 Buy the Book → Naked Economics

There is a clear distinction between optimizing and maximizing. Optimizing is about efficiency while maximizing is about getting the most.

Not knowing the definition leads to blind application. Causing us to misallocate our most precious resource: time.

This leads us to work so hard yet achieve so little, as Andy Grove once said.

Optimizing

In 2024, I slept at Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport (MSP).

Twice.

The first time, I missed it because the de-icing process took a bit too long in NYC, which ate into my margin of safety (read: layover of two hours).

By the time I landed, I barely missed it.

The second time, I landed at MSP near midnight and found out all flights were canceled due to the crash of CrowdStrike.

“If you never miss the plane, you are spending too much time in airports” - George Stigler, 1982 Nobelist in Economics

Does this mean that I spent too little time at the airport?

The question quickly becomes,

“What is the optimal amount of time to be spent on anything?”

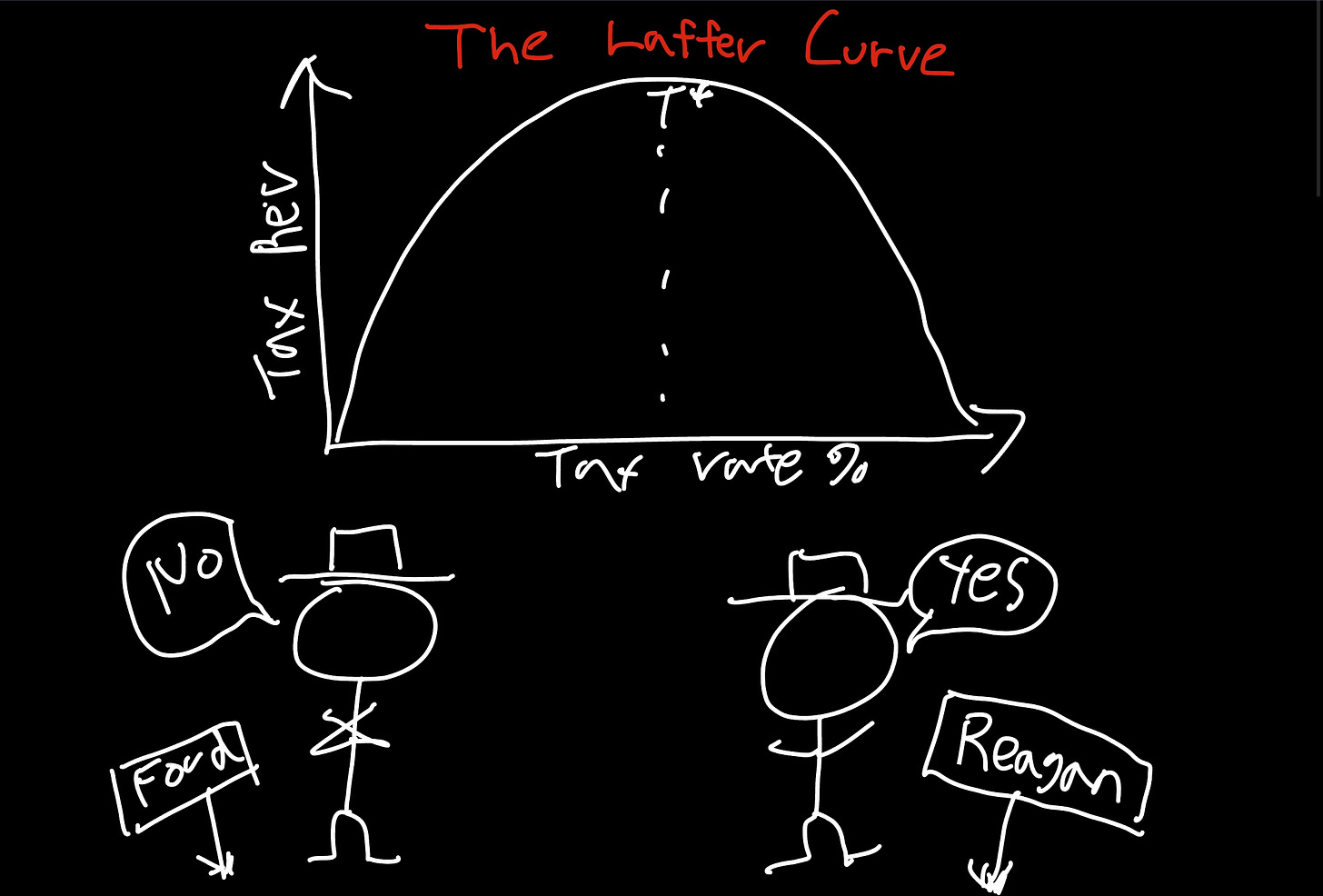

The Laffer Curve was originally used to illustrate the relationship between tax rates and government revenue. Simply put, this curve exists to prove that there is an “optimal” middle ground where rates maximize revenue.

Let’s apply this to our lives.

I believe time and energy are finite resources. Therefore, the Laffer Curve can explain diminishing returns on productivity and well-being.

Too little: If you barely allocate time to a goal (money, fitness, relationships), the return will be minimal, similar to a government with a tax rate too low to generate revenue.

Optimal: This is where the balance of time and effort leads to fulfillment.

Too much: Pushing past the optimal point leads to burnout and diminishing returns. Think of it as working 80+ hours a week which may increase output in the short run but will lead to failure over the long run. Similar to high tax rates, this will discourage productivity and lower the total tax revenue over the long run.

What’s the point?

The Laffer Curve teaches that more isn’t always better. This concept will help you decide when to optimize vs maximize your time and energy on anything (i.e., careers, relationships, health, etc.).

Maximizing

Deciding when to maximize has a lot to do with consequences as maximizing requires that you will be pushing past the optimal point for a short-term gain.

Unfortunately, consequences are subjective.

How you “feel” about the consequences is largely based on the opportunities present in your life at that given time.

Dolly Alderton highlights this in her book with the following:

“Breakups get harder with every year you get older. When you're young, you lose a boyfriend. As you get older, you lose a life together.”

Same consequence, different feelings.

Eugene Fama is known as the father of the Efficient Market Hypothesis. He argues that markets incorporate all available information.

When applied to our lives, this would mean that our human capital (e.g., skills, credentials, knowledge, etc.) has been efficiently priced into our opportunities at a given time (e.g., career opportunities, potential mates, quality friendships).

Good news is that if we desire to improve our opportunities quickly, we can. This is known as maximizing our utility.

Economics tells us that the overarching goal in life is to maximize utility

Nature is cruel because we cannot maximize everything at once (Hello, sacrifices).

After deciding what to optimize vs maxmize, comes the harder decision of when.

When = Timing

You might want to read a book that maximizes your current job // career (ex: Product Management) to improve your immediate utility. By the same token, you may want to read a book that optimizes your general knowledge beyond the scope of your current job.

The answer to “when” comes down to balancing the consumption of information that will grow as we increase our utility to get better opportunities as we age.

This means allocating some time in your daily life to acquire information that will become useful in the future rather than now.

It is similar to planting a tree today so you can sit under its shade later when you really need it. We all know this intuitively.

Unfortunately, knowing this isn’t enough.

“Simply being right about a coming event isn’t enough to ensure superior relative performance if everyone holds the same view and as a result, everyone is equally right.” - Howard Marks

Being correct about a stock market crash is the first step. The second step is arguably more important, which is to have the capital to buy assets at a rock-bottom price.

Translation?

It’s not just about calling the storm (read: market crash). It’s about having an umbrella when it hits. The key isn’t timing the event itself but ensuring you are in a position to take advantage of it when it happens.

All of it comes down to optimizing vs maximizing opportunities throughout your life.

A delicate science.

Life Happens Outside,

Su Hawn

🏕️ Wisdom from the Outpost: Take a closer look - Florida Keys, USA